How a Bill Becomes a Law

Click to view the detailed description of the legislative process.

An idea emerges.

Laws begin as ideas for governance that Council members (elected officials of the District’s legislative branch of government) formulate for the betterment of the lives of residents and the productiveness of businesses and organizations in the District of Columbia.

A written document is produced.

These ideas are recorded on paper in a drafting style developed to ensure clarity of intent and consistency of presentation.

A bill is born.

Once these ideas are developed and memorialized in writing, a Council member introduces the document by filing it with the Secretary to the Council. At this point, the document becomes a Bill (or proposed law) and is the property of the Council.

Other entities may introduce a bill.

The District’s Charter allows the Mayor to introduce bills before the Council as well. Also, under its Rules of Organization, the Council allows Charter independent agencies to introduce bills. Both the Mayor and the Charter independent agencies introduce bills before the Council via the Chairman of the Council.

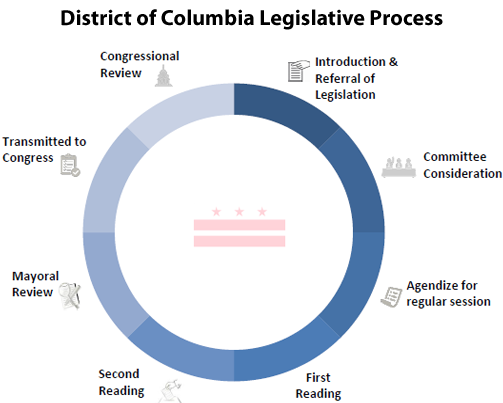

THE BILL’S PATH

The bill is assigned to a committee.

At the time a Bill is introduced before the Council it is assigned to a committee of the Council with expertise over the subject matter that the Bill addresses. A committee is not obligated to review or consider the Bill. If the committee chooses not to review the Bill during the 2-year period that the Council is convened, the Bill will die and must be introduced again when a new Council is convened in order to be considered by that Council. If the committee chooses to review the Bill, then it will normally conduct a hearing concerning the subject matter of the Bill where the committee will receive testimony from residents and government officials in support of and against the Bill. The committee may make whatever changes it chooses to the Bill. If the committee decides that it wants the Bill to become law, it will vote the Bill out of committee and prepare it for consideration by all thirteen members of the Council.

Then it goes to the Committee of the Whole.

Once a Bill is reported out of committee, the Bill is considered by a special committee of the Council that comprises all 13 members of the Council. That committee is called the Committee of the Whole, or “COW” for short. At a meeting of the COW, the Council prepares all the bills that are to be considered for vote at the next legislative meeting of the Council called to consider bills and other matters pending before the Council. The Bill is placed on the agenda of the upcoming legislative meeting along with all other matters that will come before the Council.

Becoming law.

A Bill “agendized” for a Council legislative meeting will be considered at that meeting. The Bill will be discussed by the Council members and amended if the Council members decide that discussion and amendments are warranted. If the Bill is approved by the Council at this meeting by majority vote, it is placed on the agenda for the next Council legislative meeting that takes place at least 14 days after the present meeting. The Council then considers the Bill for a second time at the next meeting. If the Council approves the Bill at second reading, the Bill is then sent to the Mayor for his or her consideration. The Mayor may take one of three actions when considering the Bill: 1) sign the legislation; 2) allow the legislation to become effective without his or her signature; or 3) disapprove the legislation by exercising his or her veto power. If the Mayor vetoes the legislation, the Council must reconsider the legislation and approve it by two-thirds vote of the Council in order for it to become effective. Once the Mayor has approved the legislation or the Council has overridden the Mayor’s veto, the legislation is assigned an Act number.

Not done yet… the final steps to enactment.

Although at this point the Bill has effectively become an Act, its journey to becoming a law that must be obeyed by the populace is not yet complete. Unique to the District of Columbia, an approved Act of the Council must be sent to the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate for a period of 30 days before becoming effective as law (or 60 days for certain criminal legislation). During this period of congressional review, the Congress may enact into law a joint resolution disapproving the Council’s Act. If, during the review period, the President of the United States approves the joint resolution, the Council’s Act is prevented from becoming law. If, however, upon the expiration of the congressional review period, no joint resolution disapproving the Council’s Act has been approved by the President, the Bill finally becomes a Law and is assigned a law number.

SPECIAL LEGISLATION (this is where things get a bit complicated).

Emergency Legislation

Because of the long and time-consuming path a bill must take to become law under the District’s Charter, Congress has provided a mechanism whereby the Council may enact legislation quickly, on a short term basis. The District’s Charter allows the Council to enact special “emergency” legislation without the need for a second reading and without the need for congressional review. Mayoral review is still required. Also, by rule of the Council, this emergency legislation is not assigned to a committee and does not go through the COW process. The Charter requires that emergency legislation be in effect for no longer than 90 days.

Temporary Legislation

Although emergency legislation allows the Council to immediately address a civic issue, it presents a situation where the law will expire after 90 days. Experience has shown that 90 days is not sufficient time for the Council to enact regular, “permanent” legislation before the emergency law dies. Therefore, by rule, the Council allows for the introduction of “temporary” legislation that may be introduced at the same time as emergency legislation and that bypasses the committee assignment and COW processes in the same manner as emergency legislation. Unlike emergency legislation, however, but like regular legislation, temporary legislation must undergo a second reading, mayoral review, and the congressional review period. Because temporary legislation bypasses the committee assignment and COW processes, it moves through the Council much faster than regular legislation. Temporary legislation remains in effect for no longer than 225 days, sufficient time for the Council to enact permanent legislation.

And then there are resolutions (legislation that does not become a law).

The Council has other legislative duties in addition to creating laws to govern the populace. Some of these duties are accomplished by passing resolutions. Resolutions are used to express simple determinations, decisions, or directions of the Council of a special or temporary character, and to approve or disapprove proposed actions of a kind historically or traditionally transmitted by the Mayor and certain governmental entities to the Council pursuant to an existing law. Resolutions are effective after only one reading of the Council and do not require mayoral or congressional review.